Covid-19 and You: Grief, Mental Health and Julian Barnes’ Nothing to Be Frightened Of

By Arpita Das

We are being told by mental health practitioners and armchair experts time and again as the pandemic rages that what we are feeling right now, this heaviness, the lassitude, the pain in our gut, is grief. As if grief were as novel an experience as the novel coronavirus. So novel, we would need help in recognising it. Instead, grief and joy have been the recognisable Januses of the human condition since the beginning of human memory. Grief has kept us afloat as a species after devastating trauma, enabling us to process the aftermath of the devastation, whether private or public, whether brought on by the experience of loss by an individual or by a community or indeed all of humanity. It is an experience, and a phenomenon, far deeper and far more empowering than its twin, joy, because it endures, even as it builds our gut’s ability to endure, and keeps us humane.

ALSO SEE: HOW THE LIGHT GETS IN: ATTENDING TO OUR ANXIETY ABOUT COVID-19

When I lost my father three years ago, and grief arrived like lightning at my side to help me cope with the desolation that followed, I turned to what I know best to try and not remain a passive observer in the process, and instead to dive in with all my senses alert and receptive — I began reading how others had partaken of the process of grief even as I went through my own. I realised then that this is what I had failed to do when in 2009, my four-year-old daughter met with a terrible accident on Diwali which was followed by a traumatic 8-month-long recovery process. My mind and heart overtaken by the need to look after my child and find the best treatment for her, I became, at that time, a passive bystander in the grieving process, and did not allow myself to experience it with awareness or intelligence. As a result, and because of that oversight, I am hurting even today.

Six months ago, I was asked by a friend who runs a remarkable series of support group gatherings for women, to curate and moderate one such gathering focused on grief. I chose to do it the way I know best. Via my curation of grief readings. Seventeen of us spoke incessantly for three hours, about what had caused us grief — the death of a loved one, estrangement from a loved one, end of a marriage, a grown child failing to understand one’s choices and choosing to stay away, regret over life choices, fear of an uncertain future, and one’s own mortality. I do believe that the most active part of my grieving for my father ended on that evening. Soon after that evening I could see my father once more as his own person and separate from myself, and I could once again see his many flaws that used to annoy me so when he was alive, which I had chosen to render invisible in the immediate aftermath of his death. My decision to not resist grief but to give in to it, and to receive it with awareness and intelligence had helped. And a large part in this deliverance was played by the texts on grief, trauma, death and loss that I had been reading over the past three years. When I was asked to write this column, therefore, I decided to put together an amble through the readings that address the phenomenon of grief in a most remarkable manner.

***

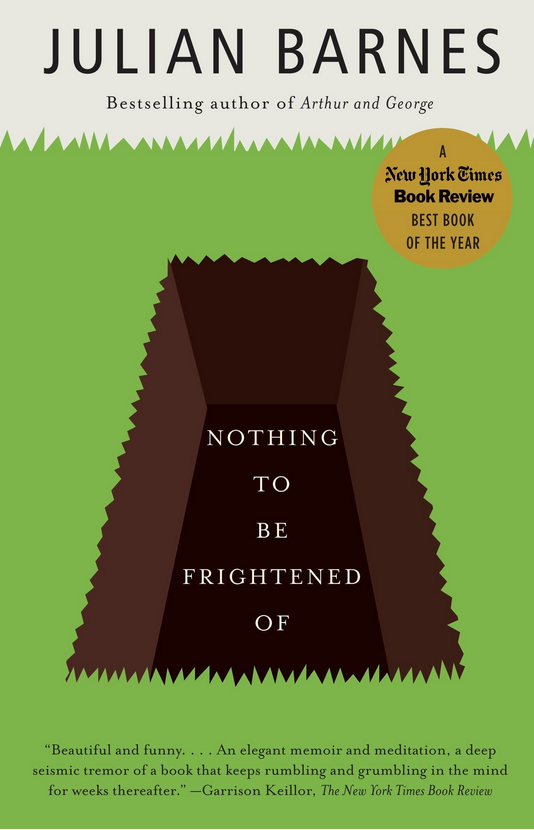

Nothing to be Frightened of by Julian Barnes is the book I return to on those mornings when I wake up feeling a tad too mortal. The end-of-the-world feeling at the base of my belly warns me that it might be a day I have to go through the motions feeling like my gut is made of jelly. A quick dip in Nothing to be… helps arm me on such days; it does not take away the fear or uncertainty, but it gives me something to work with, the awareness that I am not alone in my struggle to look my fear of mortality in the eye.

Perhaps the most unique memoir of our times, where in place of rambling on about his childhood and coming of age and tasting success, like most well-known celebrity memoirs, Barnes decides instead to talk about family, friends and his reading and writing, with one focus in mind, the most important aspect of the human condition, our mortality. There is as much recollection of childhood memories, as there is philosophising, even though his brother is the ‘professional’ philosopher, and copious amounts of laugh-out-loud hilarity and wry-smile inducing irony.

ALSO READ: MENTAL HEALTH AND BOOKS ON THE HEALTH COLLECTIVE

The bits I love the most in the book are where Barnes talks of eminent personalities – philosophers, writers, theologians, composers and physicians – who looked the moment of death squarely in the eye. Sample this, for instance:

“In 1777, the Swiss physiologist Albrecht von Haller was attended on his deathbed by a brother physician. Haller monitored his own pulse as it weakened, and died in character with the last words: ‘My friend, the artery ceases to beat.’ The year previously, Voltaire had similarly clung to his own pulse until the moment he slowly shook his head and, a few minutes later, died.”

The macabre is rendered playful, the ghoulish, utterly matter-of-fact in Barnes’s unrelentingly witty and wise prose. He applies the necessary balm to my troubled nerves with the following words:

“Would you rather fear death or not fear it? That sounds like an easy one. But how about this: what if you never gave death a thought, lived your life as if there were no tomorrow (there isn’t, by the way), took your pleasure, did your work, loved your family, and then, as you were finally obliged to admit your own mortality, discovered that this new awareness of the full stop at the end of the sentence meant that the whole preceding story now made no sense at all?”

The mind boggles as I read this bit; nope, I think to myself, I’d rather be the way I am, worrying about my mortality and how that determines the way I want to live rather than the other way around, and then, as if to reward me for my determination, Barnes delivers this doozy that makes the rest of my day look quite rosy:

…what if you lived to sixty or seventy with half an eye on the ever-filling pit, and then, as death approached, you found that there was after all, nothing to be frightened of?

The last self-indulgent line of my notes in the margin of this page reads: ‘this is how I want to be!’

You might ask, what does grief have to do with how we view or fear mortality; I would answer, at times everything. With my father gone, I suddenly felt there was no other line of defence between me and the final horizon. I hit my forties just before his demise, and the combination of the two meant that for the first time I started asking the question, is time really on my side anymore? Grief, particularly the variety that arrives by our side on the death of a loved one, is often about our own mortality, our universal, ultimate helplessness to have control. This thought is at the core of Barnes’s masterpiece; even as he explores and then admits to the lack of control with great stoicism, he leaves us with a text full of erudition and lightness that will for generations help humans make peace with their own mortality.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal

About the Author: Arpita Das runs the award-winning indie publishing house, Yoda Press. She conducts writing, editing and publishing workshops regularly under the Yoda Press Workshops Series and writes for various platforms and periodicals on book culture, publishing, bibliotherapy, gender and popular culture. You can find her on:

Twitter @arpitayodapress | Insta | Linkedin

Feature Image: K. Mitch Hodge on Unsplash

Pingback: Learning to Grieve: Through the Tunnel, with Barthes’ Mourning Diary – The Health Collective India

Pingback: Learning to Grieve with Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – The Health Collective India