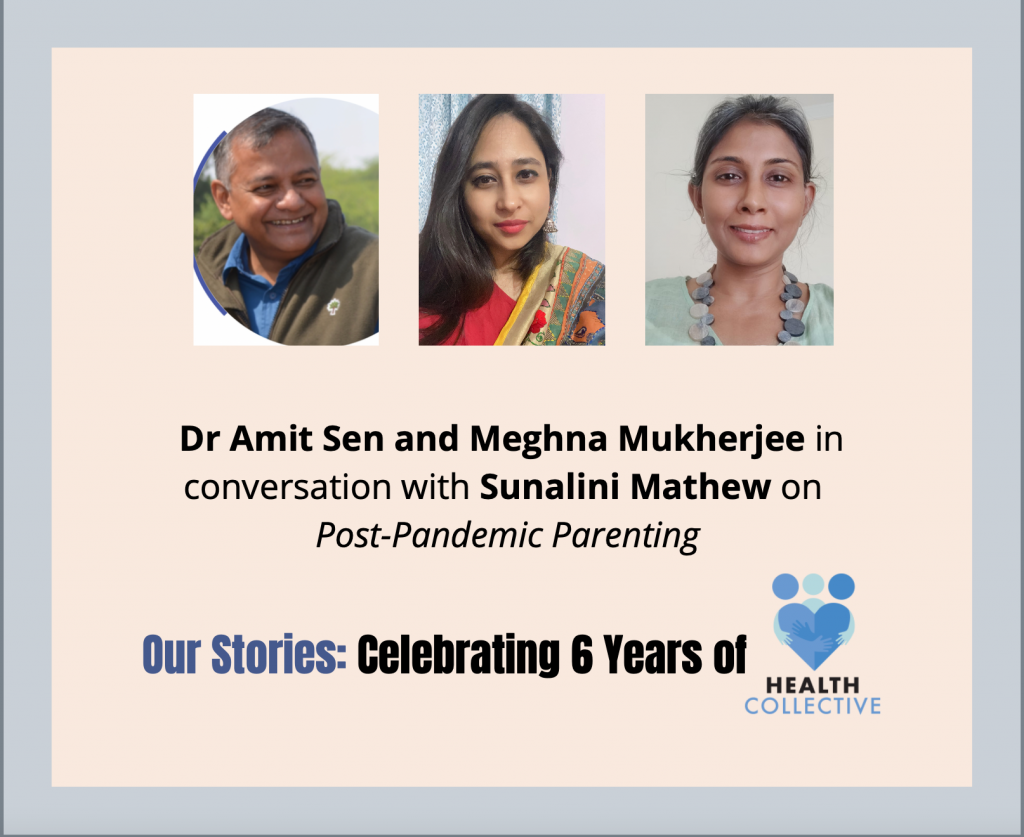

How the Pandemic Changed Parenting and What We Should Do Now

As The Health Collective turned six, mental health experts sat down to chat on real-life issues affecting us. In a panel on post-pandemic parenting, communications professional Sunalini Mathew moderated a chat with Dr. Amit Sen, psychiatrist and co-founder of Children First, an organisation that builds mental health management systems for school-goers and young adults, and Meghna Mukherjee, psychotherapist and founder of The Engaging Circle, which seeks to bring psycho-analysis of teens and children into the mainstream. The panel began with Dr. Sen’s insights on how the pandemic impacted school-going children.

Dr. Amit Sen: The first step in parenting is to acknowledge the fact that children were not able to develop in the same way as before, due to Covid-19. During the lockdown, children were not able to attend school, or social events like sleepovers and get-togethers. This impacted their social, motor and academic skills. Many class 12 students did not sit for the board exams and found themselves in college, a challenging place that many were not ready for. Writing these exams and meeting your friends are defining moments in a child’s life and help them grow. Without these, children are often left ill-equipped.

The pandemic was a very emotionally draining event. Children developed a sense of loss and mistrust of both people and social systems. In this scenario, if parents and teachers push and pressurise children, they are more likely to break. They will not be able to meet the raised expectations of their parents in these extraordinary times and this may generate feelings of inadequacy. Many may even develop anxiety and start having panic attacks. The key here is treating children with patience and empathy.

Sunalini Mathew: During the pandemic the children were in control of online spaces. Now they have gone back to offline classes where the teacher is in control. What are the challenges with that?

Meghna Mukherjee: Shifting from in-person to online classes was a very disorienting change for some students. However many welcomed it with open arms. These were children, who for lack of a better term, were suffering from social anxiety. They now had the option to turn their cameras off when they wanted and to attend classes from the comfort of their beds. It helped them as they could avoid having to interact with and manage themselves around people. Students were able to form online communities as well and assist each other during exams.

This enabled many students to get good marks for the first time and instilled in them a sense of achievement. After more than one year of online classes, most children fell into a routine. They enjoyed more lee-way with teachers and had a certain autonomy in organising their day and their learning.

After the lockdown, they were suddenly thrust into schools once again. This sudden change was taxing for most and many children reported feeling overwhelmed due to long bouts of social interaction. Isolation had made them prefer smaller groups of close friends rather than large bands of people they now had to speak to every day. Even sitting for exams became very challenging. Earlier they would collaborate with their friends to take online tests but now, they would have to memorise long chapters to actually score well. These were very sudden, and often unwelcome changes. They also lost autonomy and had to deal with authority figures.

Children need to be given a lot of time. We cannot assume that just because schools have re-opened, everything will go back to the way it was. Schools still keep getting shut due to Covid-19 cases so the uncertainty is still there.

Dr. Amit Sen: I agree with Meghna. Some children found the closure of schools comforting due to their temperament. They also had a sense of agency to switch off their camera and not interact when they did not want to. Even if they did not always make the right choices, at least from an adult point-of-view, they still had the freedom to choose. Now that we are back to the old ways, we have snatched the freedom from them. We are telling them that an adult will decide what is good for them, and that is problematic. We need to get young people to collaborate to rebuild a new normal.

Meghna Mukherjee: We need to sit down and have policies on how to have a new education set-up with children as stakeholders.

Sunalini Mathew: How do parents know if children are anxious, particularly adolescents? Teenagers usually do not come and talk to their parents about it.

Dr. Amit Sen: Parents could learn about the symptoms of anxiety and how it manifests. More importantly, however, is for them to create an emotionally safe space, where children can come and talk to them about difficult things. A way of doing this is by being transparent about what they themselves are going through. Even if parents act stoic and tough, children usually know what their parents are dealing with. During the pandemic, everyone had to deal with uncertainties and anxieties whether it was about their jobs, finances or about sending relatives to hospitals they may never return from. Children watched their parents go through this trauma and absorbed a lot of it. It is therefore the best time to talk to children about these things, since so much is changing in our lives. We have to make a proactive effort to weave these conversations into different systems like schools and homes.

Our organisation worked with a few schools run by the Delhi government. As most of you know, the Delhi government had initiated a Happiness program in schools, much before the pandemic started. This meant they were training teachers in holistic development, building a community of parents and working on the emotional health of students. This was working very well. Then the pandemic hit. During the first wave of Covid-19, teachers were able to maintain touch with the children. They would reach out to even those who did not have phones, by requesting other parents in the community to share their resources and assist them in conducting online classes.

However, the second wave of the pandemic was absolute mayhem. Many teachers lost their loved ones and went through major grief and trauma. They were not able to hold it together anymore. That was when the government reached out to Children First. We decided to assist the teachers first. We put 200 teachers into programs on dealing with trauma and grief and on how to rebuild their community.

As a result, when schools started, teachers told students that for the first couple of weeks they did not have to bring books and study, that they could interact with their friends and have the freedom to do whatever they wanted. This was surprising coming from a government school, when many private schools ran in the opposite direction and held extra classes, pressurising children to study. The teachers in the government school also tried to form systems to deal with the mental health of children and set up counselling practises there. Clearly some spaces have learnt from the pandemic and are doing their bit to create new systems to address these issues.

WATCH HERE

Sunalini Mathew: Before the pandemic, patients would usually never ask how the therapist was doing. However, now, they ask after the therapist’s health as well as their family. How has the pandemic changed the way therapy is practised?

Meghna Mukherjee: I have not seen grief of this magnitude before. The months of April and May 2021 will forever be etched in my memory. Even though my training is in counselling terminally ill people, this was different. Almost every session in those two months was about grief. I would hear statements from different people like, “My mom is in the hospital,” and “My sister is in the hospital”. And this time grief was also there in my own house. In a way, this blurred the boundaries between patients and therapists.

It changed the way I viewed therapy… I was okay with breaking many rigid boundaries. Often if someone was going through grief, they needed to know that their therapist was going through a similar struggle. I was more than willing to share my story. There is usually a strict distance between the patient and therapist but the pandemic and collective grief closed that distance greatly.

A great thing that the pandemic did was it made a lot of people more receptive to therapy. Many more people approached us during this time. Since sessions were conducted online, it also made access to therapy easier. This whole period increased the conversation around mental health. That was the post-traumatic growth post the pandemic. Although there was post-traumatic stress, there was also growth in conversations around mental health.