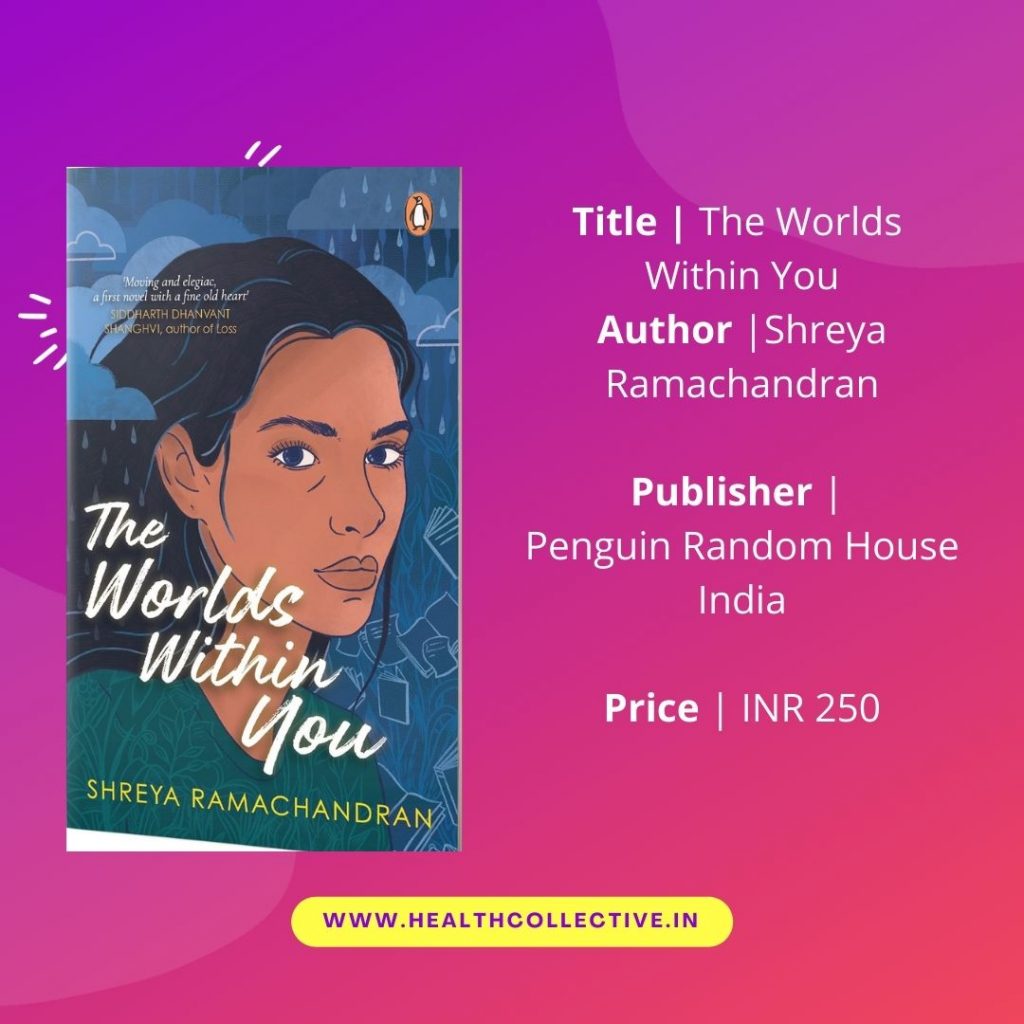

Young Voices: Shreya Ramachandran and The Worlds Within You

Following is an e-interview with debut novelist Shreya Ramachandran, author of The Worlds Within You. Do read a short excerpt of the book here.

- Tell us a bit about what led you to write about The Worlds Within You?

It’s strange because I always loved writing, I was always ‘known’ by my love of it, so on some level I felt my work and future career would come from it. But writing a novel didn’t occur to me, though I loved reading them. Maybe because I didn’t know what it was that moved me to write something so long and all-consuming. I did NaNoWriMo for many years and in 2016, wrote the first draft of what would become The Worlds Within You.

What moved me to write was, when parents and families think children don’t have ambition or are lost or on a gap year – children aren’t the lackadaisical, entitled figures that they are made out to be (as I found out myself). It came from this impulse: how does the person who is confused and trying to communicate, on say, a gap year, feel, and what are those interactions with family like? I’d read American versions of this dynamic (for instance, Leigh Stein’s novel) and I wanted to create an Indian version that felt true to my experience – and perhaps to others’, not just Indians’. But rooted in the reality of what I understand family conversations and personal conversations are like. There was a temptation to see that written out and in the world.

- What draws you to write and talk about mental health? And why is it important to have these conversations?

My own experience with anxiety, starting in my early twenties but really going back to my teenage years now that I think about it, and finding spaces to have conversations about mental health. I didn’t intend to write about the diagnosis of a mental health disorder in my book – it just happened, perhaps because of my own preoccupations and the huge role it played in my life.

I think it’s important to have these conversations because mental health, or ill-health, is such a huge part of how everybody experiences their daily life. It affects perception, relationships, living. And people don’t often want to share how they feel or what their experience has been. It’s almost as if everyone has two lives: the one they show, and the one they live. And conversations allow for a glimpse into the latter. At best, it makes us more aware of the world around us. And it helps us all feel we are not alone. We find community or at least a glimmer of connection.

3. We learn quite early on that the character of Ami is struggling — she’s taking a break from university, she’s worried about almost all of what she’s feeling, she’s feeling like she’s forced to “smile wide” for her family — and realises much later how concerned they are for her. It was very skilfully done, showing the weight of that guilt she feels for not being ‘normal’ and sort of being ‘a drag’. Can you elaborate more on this and why was it important to depict?

Thank you so much! I think this just felt very true to who Ami is. Often we are preoccupied with how we feel; we don’t realise those around us are impacted by it too. By what life paths we are on, and which might be meandering, or stuck. That guilt makes Ami who she is: she is as if nostalgia and sadness were personified in a character. It also, however, makes her closer to those around her. It allows her to acknowledge that her experience impacted others.

It was important to depict for me because I am so interested in finding answers to questions like: how does your experience affect your family, your friends? How are you shaped by people around you? What does it take to support someone? What is the emotional toll of caring? How do you come to terms with who you have been and therefore what you do?

4. One of the most central figures in the book is Thatha, the grandfather who passed away — Ami is struggling with her own grief, and mourning in her own way and feels everyone else has “processed” it. Can you share more? This is something that will likely resonate with anyone who has lost a loved one.

This is something I have experienced in my own way too. The ‘smallest’ grief or loss can stay with you for years. And while, yes, Ami feels everyone else has ‘processed it’ – it lingers with each of them, in their own way. It was wonderful to write this and have others – editors, first, then beta readers, then readers – say – ‘we understand this feeling.’ Because in my book it was a question I was putting out. Can you feel sad about a loss like this, years after the fact? Can it impact you? Am I correct in my estimation? And people have said – yes, you are, it can, I feel that too.

I feel the loss of a loved one is not an event – happened, and done – it is more a colour. So that colour will be with you forever. In how you see the tints of the world. It comes, it goes, it comes again. That has been my experience. And, I think, that of others too. It changes everything.

Shreya Ramachandran

5. What’s a message you’d like readers to take from the book, if any?

If I may borrow from Coldplay’s song A Message: ‘you don’t have to be alone.’ But if that’s too cheesy, let me elaborate.

You are important. Your feelings: everything from when you were thirteen that you scribbled in your diary – is important. The way you perceive your hometown, the space around you, the gulmohar tree, the things people said to you years ago. All of them make you who you are, and people have their own sum-of-accumulations like this. If you’re lucky, you get to share in that with someone. And if you can find a way – through writing, or through any other means I am less comfortable with – to put words to this accumulation – it can be rewarding in wonderful ways.

6. What is one myth on Mental health you would like to bust?

It isn’t a capital-c Conversation. People are affected by it all the time – disorders; depression; low moments; just affective changes. You should talk about it. And yes people will disagree – this is the ‘wrong’ way to talk about it; this is ‘too much’; ‘too less.’ And please, let’s not say we should talk about mental health like we do physical health. Because we also don’t talk about physical health enough. We hide our symptoms. We hide how we feel. We hide how we are impacted. We are afraid of doctor appointments. These things take money; energy; life; soul. These things are at the heart of all our experiences. But we don’t talk about it. So the myth I’d like to bust is: it’s an ‘event’ for one month in the year. In reality, it’s everything. All the time.

7. There are some really great pop culture (music and lit) references in the book (I love the Oasis shout and The Verve, to name two, but you also discuss Keats and other poets) — what are some of your influences?

Thank you!!! Some of my influences were definitely the Leigh Stein novel I mentioned – The Fallback Plan – as well as early writing influences, Hemingway and Salinger. I loved Judy Blume’s novels, especially Here’s to You, Rachel Robinson; and Jacqueline Wilson’s novels, especially the Girls series. I love Anjum Hasan’s Difficult Pleasures; Elizabeth Strout’s Olive, Again; Rilke’s everything he wrote, especially The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge which inspired me with this book. I also love Proust (though I am yet to finish the series!). In recent times I have loved discovering Russian literature. I can’t directly find a connection from it to my own work but it has inspired me immensely. I love the gentle imagination of Vinod Kumar Shukla’s writing (which I do have to read in translation).

Music is huge, too – the artists you mention included. I love certain songs by the Arctic Monkeys, The Verve; I also love certain specific songs that take me back, which might not objectively be ‘good,’ including Wherever You Will Go by The Calling.