From the Asylum to the Mental Hospital: Tracing India’s Journey

By Amrita Tripathi

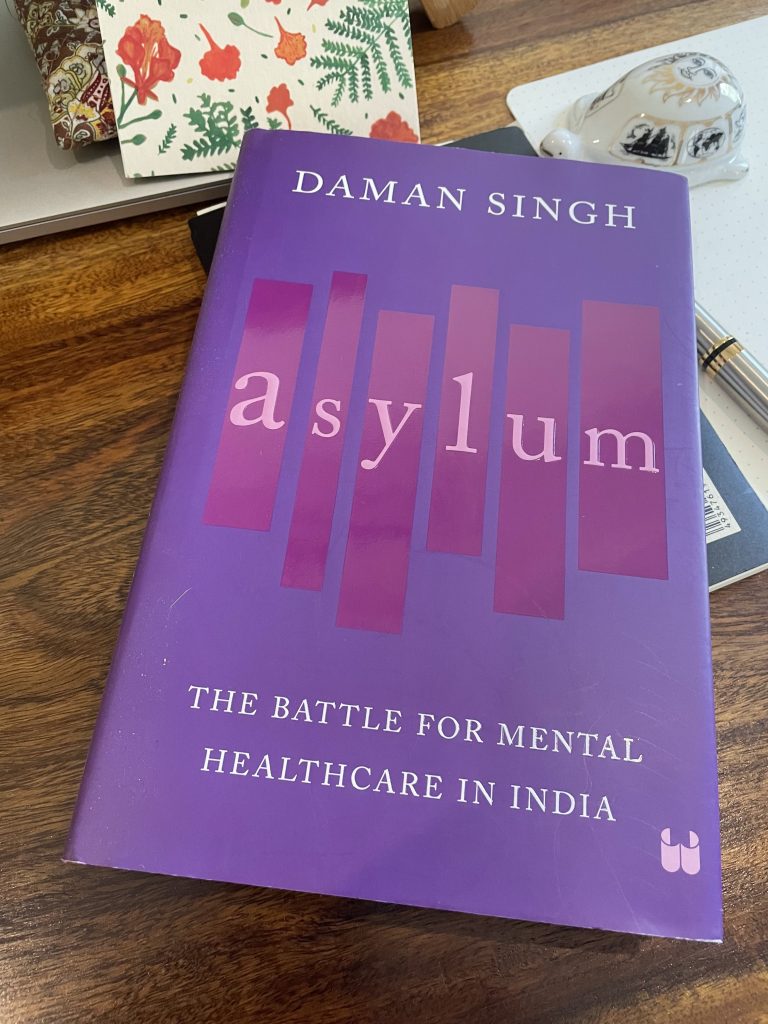

Author Daman Singh set out on an ambitious quest to research and understand India’s journey in the mental healthcare space — from the ‘lunatic asylums’ of the 18th century, to the emergence of a more scientific and humane approach in the early 20th century. We did an e-interview for The Health Collective about her new book: Asylum: The Battle for Mental Healthcare in India.

1) What inspired you to write Asylum?

Quite by accident, I came across some intriguing references to mental hospitals in British India. So I started to read up on the subject. I found a number of books and articles about asylums in the 18th century, the 19th century. These were places where the “insane” were confined under harsh, cruel conditions. It was only in the early 20th century that ideas began to change. That’s when “insanity” was recognised as an illness that could be treated – as well as cured – in a humane and scientific way. I wanted to know more about what happened next. How did things change on the ground? How did asylums become mental hospitals? And how did mental healthcare evolve to what it is today? Very little has been written about this side of the story. So I decided to discover it for myself. That’s what led me to write Asylum.

2) Can you share a few things you’ve learned during your research and interviews, and/or anecdotes that have really stayed with you?

When I was working on this book, friends would ask me what it was about. As soon as I said the word ‘asylum’ or even ‘mental hospital’, there would be an awkward silence. Or a baffled look. Or an expression of alarm. I tried not to let this discourage me. Most people have a very scary image of a mental hospital. Actually, I did too, till I visited the Central Institute of Psychiatry at Ranchi.

It was quite a walk from the institute’s main gate to the library, where I was headed. This gave me the chance to look around. The campus is huge, with paved driveways, lovely lawns, shady trees, and scattered buildings. Doctors, nurses, and support staff were going about busily. Patients were roaming about freely. Some were sitting in the lawns, chatting. As I stopped to ask for directions, two patients strolled up. One of them asked me if I was a patient or a visitor. I told him that I was a researcher. He nodded, and the two of them strolled off. The library was excellent, the staff were most helpful, and various students were studying quietly. Some doctors spared a great deal of time to answer my questions. My visit was short, and I didn’t see the whole campus. But what I saw was not scary at all. It was, in fact, very pleasant. I hope that this is true of other mental hospitals too.

3) Why do you think it’s important to talk about mental health and mental illness in India?

For a long time we didn’t know how many people were affected by mental illness in India. Now we know – it’s about 150 million. This is a huge number. Yet only 1 in 5 persons gets treated. Why is that so? Some don’t get diagnosed in the first place. Some don’t know about treatment options. Some avoid treatment due to the fear of social stigma. Today there are a wide range of therapies that can enable a person to deal with mental illness, to lead a meaningful life, to live with dignity and respect. We need to talk about these things. We also need to talk about how families, friends, schools, colleges, employers, and communities can be more sensitive, more supportive.

4) I’ve started reading your book, and it’s quite fascinating, that so much depended on individuals (the superintendent of the asylum) — can you share a bit more about some of these characters, the alienists, the folks like WSJ Shaw and others?

In colonial India, certain mental hospitals were run by doctors who had specialised in mental disorders. These specialists were known as “alienists”. Luckily for me, some alienists were prolific writers. Their reports, articles, memos, and letters tell us a lot about them and their work. Like other alienists, Dr WSJ Shaw believed that “lunatic asylums” ought to be renamed as “mental hospitals”. When he proposed this in 1916, the idea fell through. But he kept pushing the case till the law was amended in 1922 to allow the change in name. This was an important step to modernise mental hospitals. Then there was Dr CJ Lodge Patch who changed the rules in his hospital so that patients were treated decently. When he found that the attendants were not cooperating, he decided to recruit former army sepoys. These new attendants were disciplined and used to following orders. As a result, the older lot were sidelined and gradually got weeded out.

Dr OAR Berkeley-Hill insisted on giving his patients as much freedom as possible. For instance, they could go outside the premises for walks or even for shopping. He introduced all kinds of recreation, including “ladies vs gents” hockey matches, and started a special programme for occupation therapy. He also kept track of patients after they had been discharged. Dr JE Dhunjibhoy took great interest in experimental treatments in Europe and America, and tried them out in his hospital. He was one of the few alienists to be published in Lancet. These are just a few snippets from the book.

5) Can you share with us your thoughts on where things stand when it comes to mental healthcare in India, going into 2022, given the mental healthcare act, for example and what seems to be an increase in interest/ attention to the field?

To be honest, I’m not sure where we stand today. It’s true that we now have a progressive mental health policy, an ambitious national mental health programme, and an aspirational mental healthcare law. Healthcare services have spread from mental hospitals to general hospitals, and from inpatient wards to outpatient clinics. But we still have a huge shortage of specialists – psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, counsellors, etc. So, millions of people still don’t have access to mental healthcare.

Today, society understands mental illness far better than it did, say, 20 years ago. Community programmes, support groups, campaigns, and internet resources are certainly making a difference. I get the sense that young people in big cities discuss mental health issues quite openly. This needs to happen more often among other people, and in other places. Once it does, society may become more supportive of people with mental illness. As of now, we have a very long way to go.