Can Understanding Impermanence Help us Cope with Life?

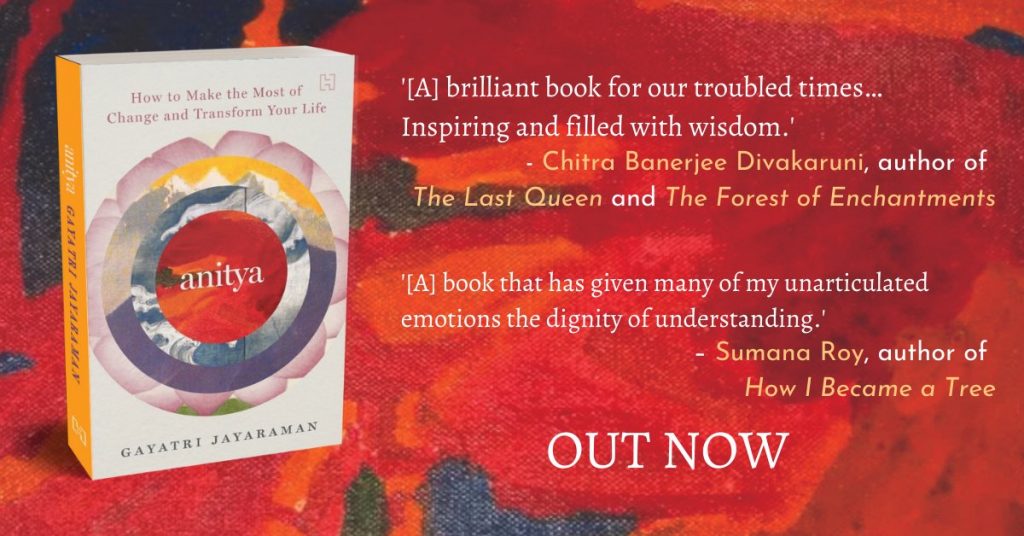

Gayatri Jayaraman is a mind body spirit therapist and founder of Shamah | शम: Jayaraman is a mental health columnist for Money Control and the author, most recently of Anitya: How to make the most of change and transform your life. She was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize for Poetry 2021, and has two children’s books on coping with emotions out in 2022. You can dig in to an excerpt of her book right here before reading her e-interview below.

1. What led you to write this book?

The pandemic began to rear its head in March 2020, when I was in the last week of my Post-graduate Diploma at St Xavier’s Institute of Counselling Psychology, Mumbai. As we went into lockdown, the previous year and a half of vipassana meditation along with college-mandated therapy sessions kicked in. People around me began to crash into despair. I sat on this life-raft of inner work realising I was in a position to start throwing out ropes to those in the water. I began to offer counselling sessions online and in the first three months, I took over 60 sessions per month. People from Guwahati, Coimbatore, Indore, single and married women, battling loneliness, abusive or taxing relationships, men whose jobs, enterprises and incomes were in jeopardy, students stuck without their parents, elderly women who lived alone, NRIs stuck without access to elderly parents, the grieving, even foreigners unable to get appointments in their overworked mental health systems, reached out. The need was overwhelming but I found myself unperturbed, like I had some deep calm inside me. I kept asking my therapist: ‘Is something wrong with me?’. One option was I was self-numbing. But the other was that the processes I had been through really worked. That it is in fact possible to surf an emotional tide with effective therapy and meditation.

My son was scheduled to leave for college and I was scheduled to leave for NYU for my Masters in Applied Psychology that year and we both had to postpone our plans, like so many others. Somehow it didn’t seem to me to be unfair or ill-timed. I was already on a different path due to this experience. I had begun to shift from the Western clinical model.

Indians face real stigma when seeking a mental health session. Many were choosing my ‘meditation’ sessions and asking for counselling, or taking counselling sessions and making their payments as ‘meditation class’ so their families wouldn’t know. Meditation was not only an effective tool in itself, and it not just bypassed the stigma, families were encouraging each other to take to it.

I knew then I needed to work with a combination of mind, body, and spirit, retrieving meditation, counselling and body work from their silos and use them in an integrated way. I knew from my overseas clients, in what ways the Western model simply wasn’t working for them. So, I began to write Anitya, which combines these mind, body and spirit practices, and allows people to identify with cases and interventions that work for them. Essentially, counselling, Buddhist and Hindu meditations, yoga and Qi gong.

2. You’ve shared some really interesting stories in the book, including some of your own journey — can you tell us a little bit about how you transitioned from journalism to therapy — what motivated you? And if you can share a little bit on how your practice encompasses more than traditional psychotherapy?

Most therapists come to mindfulness through CBT, but I came to counselling through rigorous meditation. I had wanted to do a vipassana course ever since my brother first recommended it to me 15-20 years ago. But as a single mom, leaving my son without even telephonic contact was just not an option. The day he completed his 10th Board exams, I booked myself into the only course with dates available, which happened to be in Sikkim. I have recounted in detail how transformative the experience was in Sit Your Self Down, a personal precursor to Anitya.

In brief, it was painful, funny, revelatory, and it peeled away years of subliminal motivations of grief, rage, blame, and connected so many dots for me. I saw how I, not others, had shaped my life. I saw how I had gotten in my own way. I saw how one act or thought led to others, and causes begat consequences. I saw how to free my mind from this cycle. I can’t even explain the clarity that vipassana gave me. Today I can tell you I feel no anger, hurt, self-woundedness. I wanted others to have this.

I knew many like me didn’t have the time or freedom from a 10-day commitment so I wanted to offer meditation-based counselling. But I also didn’t want to be a quack. I think vipassana is great for most people but if you have severely repressed trauma, you need to deal with all that first, else it can hit you really hard. There’s no gradation in vipassana. So, I knew I didn’t want to work with vipassana per se but with gently easing people into various basic meditative techniques that work for them so they could integrate them into their daily therapeutic practices.

It would be vital for me to have counselling skills for this. I first wrote to the Institute of Indian Psychology at the Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry from where Matthijs Cornelissen re-directed me to Pune, where there are great courses at both Fergusson College, Savitribai Phule University and WCCLF. I applied everywhere I could think of, including TISS and St Xavier’s not knowing if they would consider someone my age, I was 43 by then. I had quit my job, and in the week before it ended, I received the call from Sujata Abraham – St Xavier’s had accepted me. One course led to the next and as they say, your teachers find you. I just submitted to the process.

I have been a writer all my life, but it is only after studying counselling skills I understood the power of words. The only tools a therapist, counsellor or psychologist has are words. We use them to clarify, empathise, affirm, negate, confront. These words in themselves release you from burdens. A client will latch on to even the subtlest shade of meaning. If someone is grieving and you tell them, ‘You must be devastated’ they will correct you. ‘No, I’m just numb’. That degree of the word, only counselling opened me up to. Meditation gave me the deep value of silence. So I don’t think I transitioned away from the writerly life. I just understood its range and power clearly.

Until then, I was reckless with my words. I think in the social media world, a lot of us are, words are weaponised.

In both Buddhism and Psychology, the fundamental principle is ‘Do No Harm’. I am very conscious of that now. It changed how I operate in the world. The balance between these two, meditative silences and an intentional use of words, craft my practice. The Western model of psychotherapy operates in denial of the spiritual side. They bring it up only in geriatric psychology as if a man can find faith, belief, hope and purpose in the end of his life without ever thinking of it during his lifetime. We are complex beings and a bundle of our belief systems, both irrational and rational. Anyone who ignores the irrationality of a person, especially in mental health, is only treating half the person. Numbers, statistics and evidence are Western scientific methodology. It’s one language of the world, not its medium of expression. Indigenous cultures have always had oral traditions, not written or numerical. Its intrinsic to how some communities think. They also derive evidence from lived experience, inference, contemplation, elimination, and other techniques. We can’t only accept the truth of the latter when it fits in with the former’s vocabulary, equipment, research methodology and teaching mechanism. Reality is not truth, because each one’s reality is their own. To an irrational man, his reality is his truth. Our role is to meet people where they are and help them find their way through their own mental systems, not superimpose ours. Instead we psycho-educate them so their vocabulary fits our lexicon. Then we will declare them ‘normal’. This is upside down. Our minds leave deep impact on our bodies, and this act of witnessing ourselves is largely unconscious. How do we bring that into conscious awareness? You have to witness yourself in your own reality, not in that of a lab. You can’t answer, ‘I’ve no clue why I said that or did that’ without comprehending how the irrational parts of your mind work. You don’t see yourself as a whole if you’re only looking for the bits you have pre-labelled good or appropriate or valuable. My irrationality is probably more accountable for my flaws, mistakes, detours and has a greater role in shaping me than my rational side, which seems to desert me whenever I need it. The instinct defaults to the irrational mind and finds its cues in the unconscious and subconscious patterning. That is what I work with. And the Buddha’s work is one of the few systems of knowledge that gets to the root of this. He classified over 120 kinds of mind and 52 mental factors apart from errors of perception, cognition, illusion and the causal link between them. He maps exactly where emotions arise and how they play out. Even Western psychology only studies some of these aspects in bits and pieces.

3. I was really taken with this insight you share referencing Soto Zen Master Shunryu Suzuki (thanks for reminding me of the name!) — about having the front and back door of our mind open, and letting our thoughts/ emotions in, but not necessarily serving them tea! Can you share some more?

This is an essential meditation technique. Psychology constantly tells us to accept our feelings, but it’s only when you get into meditation that you understand how to accept one’s feelings in practice. Until you actually have to sit with your body and your mind and witness the impact your reactions have on them, it’s all theory.

In Theravadan Vipassana, in Zen’s Zazen, or the Mahayana Shamata, sitting is simply about acceptance. When you sit for 15 minutes let alone 15 hours a day as one does in longer retreats, you see that it becomes so difficult to accept the running of the mind, the shifting of the body, pain, even just at the gross level. How do you accept your thoughts, your rising emotions provoked by memory or anxiety? Psychology deals with it at a surface level.

Someone or something will provoke you, just don’t react they tell us. But how? We are so used to reacting. What the Buddha found was that reaction on the surface level of the mind is just the symptom. When you meditate, you see the outward expression is only the end result, the expression of reaction. Let’s say you’re passing a bakery and you get the smell of fresh bread. Observe that it first hits you as a sensation. You find a sensation in your stomach, on your tongue, in the back of your throat. The mind recognises this cognition as desirable, then it stirs emotions, emotions stir thoughts of wanting. Then you act to buy it or ignore it. What you do is only an end result. If you don’t train yourself not to react to the sensation, chances are your ability to not react in action will be limited. This is why most of us know what we should and shouldn’t eat but succumb anyway. Same with anger. Someone says something, you don’t want to react, but it hits you in the feels as we say, and then emotions rise, thoughts, then expression. You can’t control expression alone, you have to go to the root. This is the Buddha’s technique, that when you understand how the mind works, you can train yourself not to react. And this is a liberating path, because it frees you from being subservient to the direction of all external provocations. So it’s a simple line by a true Zen master, but like all things Zen, the philosophy is deeply complex and the result of layered mind studies. When the thoughts come, not feeding the thoughts or serving them tea, is a mind training that takes a lifetime, or many, to conquer. If we can do that, we all become Buddhas. The good news is we can all do it.

ALSO READ: COVID19 AND YOU

4. It’s been a difficult few years for a lot of people due to COVID-19 — do you have a few messages in the book (or otherwise) that you’d like to highlight that could speak to some of what people have gone through (keeping in mind of course, that there has been a range of trauma and suffering, grief and devastating loss).

I think the message of the book is fundamentally Anitya, Impermanence. We struggle because we hold on to the notion of permanence and strive to keep the illusion. You look at a leaf and think it is solid. You look at it under a microscope and realise it’s all cells, fluid and mutable. Then the decay or the transformation of the leaf ceases to surprise you. It’s only when you assume it to be solid you are caught unawares. This is why witnessing Anitya is the basis for coping with change. When you see, not as a theory, but in practice, the microscopic shifts that occur moment to moment, you don’t expect things to stay the same. You see they simply cannot. It’s not personal, a punishment to us, impermanence is a basis of existence, all things coming into being must also end. This is the difference between people longing for a past or a notion of finality or stability that simply cannot exist, and accepting the fluidity of life. It’s a shift in perspective that makes all other shifts palatable. Yes, there is grief, there is death, there is loss, there is cruelty, separation, violence that is incomprehensible, we’re witnessing all these around us every day. Take the violence, that’s a bitterness that comes from people who cling to eternality, supremacy, who are frightened by losing a position. When we don’t know how to release what is passing, the anger, ego and insecurity erupt. Witnessing Anitya shouldn’t make us passive to our environment either, but compassionate and participative. We know things decay so we enjoy them in the time we have them, we make moments precious, live them to the fullest, do what we can and release what we can’t control. We live and love intensely because we know moments are finite. Anger and rage become futile because we see the ways in which they harm us as much as they harm others, bodily, viscerally. Every word can liberate or wound so we choose our intention. You walk down the street and see a rainbow. You know it’s just an interplay of light and water, gone the moment a cloud shifts, but that doesn’t make it less beautiful. You can take it in, smile to yourself, and cherish it when it’s gone. If there is grief there is grief, and you feel the intensity of that grief fully too, but also, there is joy. As the cycle turns, we take in life.

5. What do you make of these moments in life which you talk about – let’s say the mid-life crisis, or the layoff from a job, or the loss of a loved one – What’s the key to making our peace with some of these and embracing that change?

We imagine we will be at peace when life starts going our way. But life will always not go our way. Most people who give off the impression that their life is perfect are holding that image at great mental health cost to themselves, compromises, projection, suppression, simmering under their facades. We are peaceful when it ceases to matter to us whether life goes our way or not. People are always asking, ‘What do I do?’ to have a better life and they don’t want the answer ‘do nothing’. How can we do nothing? We build, we accumulate, we amass, we want. We believe the more we do the more certainty we will have. But as we see around us, those who seem to have it all are the most insecure because now the fear of losing all we have sets in. All our grief comes from losing this control over things – jobs, relationships, homes, friends, guarantees of undying love and long term commitments that nobody is in a position to guarantee us. Like breath, watch it come, watch it go, with detachment. Don’t grab, don’t hold, don’t resent the passage of phenomena and time.

The amount of energy we put into keeping things the same is what turns us grey and anxious. What is same anyway? We don’t even step into the same river twice. You can go back to an office you worked at a day later to pick up a PF form and feel like an outsider. Our partners change on us and we don’t recognise old friends or exes anymore. We revisit old homes, old schools, and are amazed by who we were. We fight to keep our CVs seamless and miss out on our kids’ first steps, or time with parents we would never get back.

Jiddu Krishnamurthi said, ‘My truth is I don’t mind what happens to me’. As His Holiness recently tweeted: “If you are motivated by a wish to help on the basis of kindness, compassion and respect, then you can do any kind of work, in any field, and function more effectively with less fear or worry, not being afraid of what others think or whether you will ultimately reach your goal.”

When we view life as a vast accumulation of experiences, we don’t worry so much about the cohesive narrative we are building to someone else’s version of what success looks like. We all know people who have gotten their first job at 60, returned to college at 45, gotten married at 76, dropped out at 16, adopted kids at 50 and came out at 35. Who is to say what is the right timeline to live to and where does the mid-life crisis occur then? It only occurs when you live to someone else’s linearity, never in your own.

6. Finally, what are 2-3 Myths on Mental Health and Mental Illness in India that you would like folks to be done with in 2022?

1. That there is only one way to mental health: Mental health is finding the therapeutic route that works for you. This whole battle over CBT and DBT and psychoanalaysis and talk vs medication, or this meditation technique vs that grounding technique etc is really banal. If no two human beings and their minds are remotely alike, no one methodology should apply to more than one person. As therapists, counsellors, psychologists we have to be able to embrace the expansiveness of techniques and work with the client, not bend him to our training and methodology.

2. All beyond the evidence-based is to be shunned: It is as much of a faith trap that mumbo jumbo is. We are not obliged to believe in science any more than we are to believe in a mantra. Ask if it works for you. Test it out in your own lived environment and if it doesn’t work, keep looking. This is exactly what the Buddha rebelled against. They told him you can’t get to where we are unless you train in our knowledge systems, use our language, recite our chants and participate in our debates. And the Buddha was like hmm, let me figure this out for myself and sat under a tree and didn’t move until he did. It’s your mind, your intellect, your life, your experience. It isn’t invalidated just because it didn’t check off against a research paper. We need to be done discounting those the evidence hasn’t taken into account and see it as one more tool of exploring the mind, and not the only one.

3. That you can ignore, deny and suppress spirit, philosophy, and the ways of the so called irrational mind: The world will never be entirely rational, nor should it. Fantasy and delusion have their own place within the mind. They serve a purpose. God is a huge crutch for many people. If you want to take away their crutch, give them something to believe in instead. And don’t say science, because you’re asking for faith again, and a man’s faith has to have somewhere to go, or he is left in despair. I feel this is a huge part of suicidal ideations that is ignored. In my experience, what they’re asking is ‘what can I believe in?’ and the world is not giving them an answer. This is also one effect of over rationalising the mind. Belief and faith, our ability to tell stories and believe in an ending matter deeply to the most primal part of human beings. As the world becomes harsher to us, whether in terms of climate or the loss of icons, the prevalence of violence, we will begin to see more people turn to the so-called irrationality. This is also a support system of the mind. Better we understand how and why it emerges, and how it operates, rather than shutter it down.

Views expressed are personal.

Anitya is out now and available on Amazon India and at local bookstores.