Parenting in the Time of a Pandemic

By Vanita Singh Fernandes

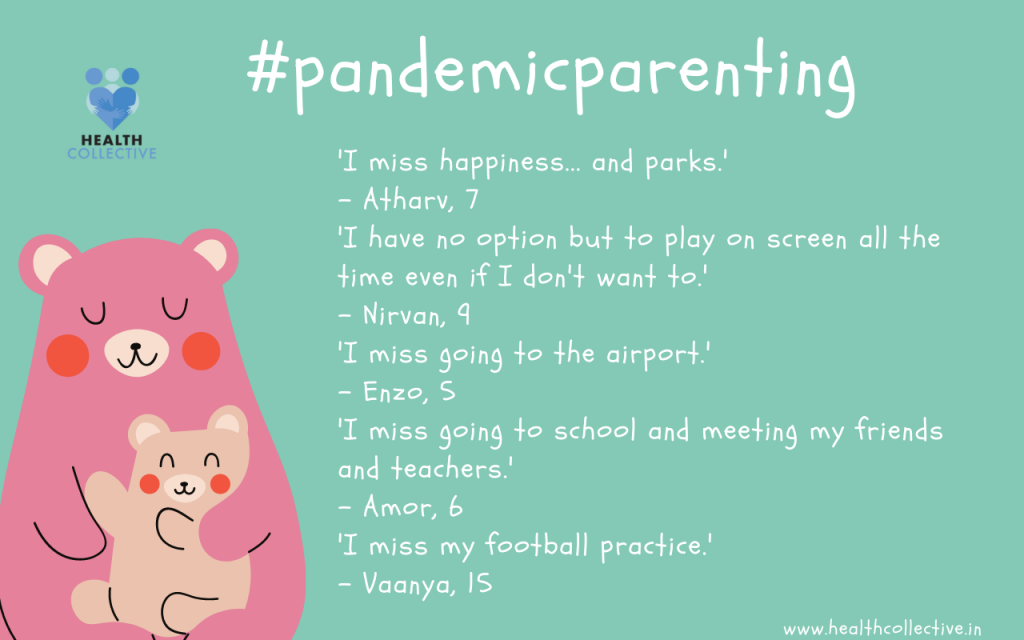

‘I miss happiness… and parks.’ – Atharv, 7

‘I have no option but to play on screen all the time even if I don’t want to.’ – Nirvan, 9

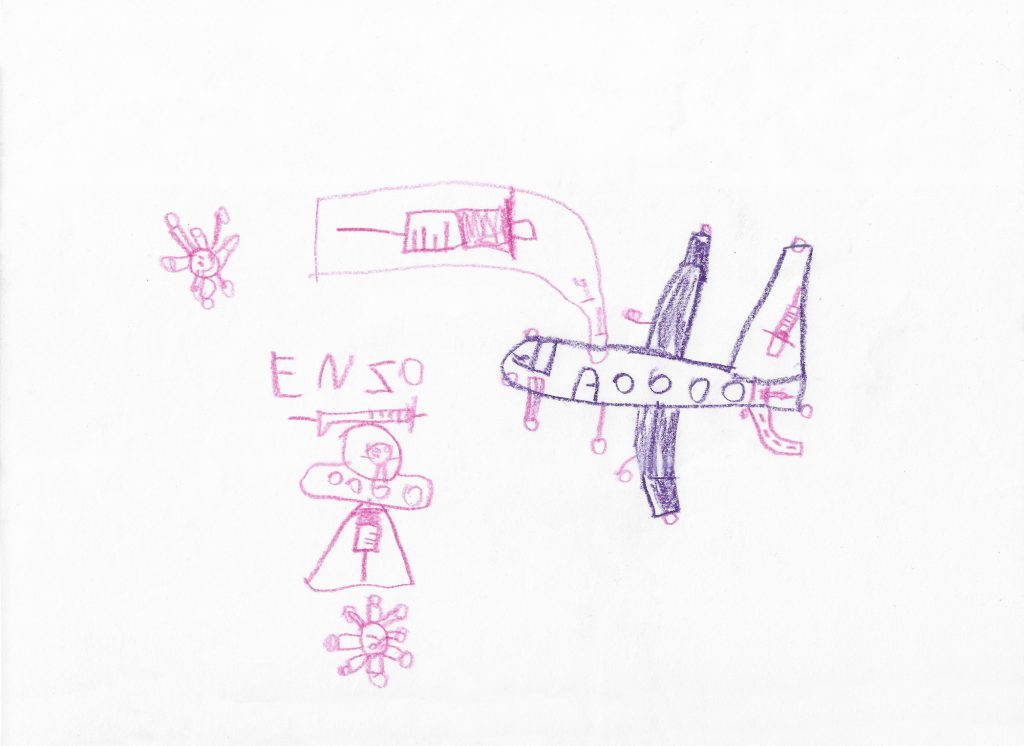

‘I miss going to the airport.’ – Enzo, 5

‘I miss going to school and meeting my friends and teachers.’ – Amor, 6

‘I miss my football practice.’ – Vaanya, 15

These are just a few voices, but concerns of many children, sharing what they miss the most from the time before Covid-19. Before it dramatically affected their lives, before they were limited largely to the confines of their homes, without much interaction with other children or for that matter, adults. Before schools squeezed into and onto screens and play areas and parks were reduced to a memory. They had to mask their faces and in turn, also found themselves masking their feelings and emotions owing to the situation. Meanwhile, parents too were faced with this once-in-a-lifetime situation without any blueprint to refer to.

Parenting is challenging. Parenting in the time of a pandemic, doubly so. “As a parent, my child’s worries become mine. Work at home increased since we were short-staffed and arranging quality time with my child became even more important but difficult,” the Mumbai-based Rameet Gidwani, mother of a 7 year old who also owns and runs a clean confectionery brand, Lavender & Cacao, tells The Health Collective. “Being a working parent, I had to switch too many roles which I felt like I failed at very often and blamed my parenting skills, leading to self doubt.”

With families at home, the help away, and schools closed, many middle class city-based parents (especially mothers) now found themselves on 24 X 7 parenting duty (if it wasn’t the case already). This, in addition to the added domestic work load and their professional demands, all culminating in an increased but invisible mental load. “There are days when it’s very overwhelming,” adds Gidwani who often finds herself in a ‘need of a break’ so she can continue functioning.

Founder of letsraisegoodkids.com, parenting columnist and mother to two daughters, Geetika Sasan Bhandari had to master the balancing act when her 14-year-old contracted Covid soon after the family’s move (from their Gurgaon home) to Nigeria in October 2020. Bhandari had to juggle multiple requirements – isolate her husband, her 79-year-old mother-in-law, ensure meals and medications were given to every room, and continuously remind her daughter to check her temperature and oxygen levels. A few months later, her daughter fractured her foot. “All of this, plus everyone being home, fruit/snack breaks, catering to two different school timings, a child who was on a cast from thigh to foot etc. took a toll on my mental wellbeing,” confesses Bhandari. When her daughter was isolated and down with Covid, Bhandari had concerns about her daughter’s mental well-being and actively worked towards keeping her child’s spirits up. Bhandari’s daughter wasn’t the only one; for most children under lockdown, there were fewer than ever options to look to, to keep their spirits up. And with schools, friends and playgrounds out of reach, children increasingly turned to screens.

“Before the pandemic I had really worked hard to make sure my kids didn’t have that much access to (a) screen. Today after almost a year and a half at home, unfortunately both my kids are quite addicted to the screen,” says Aloka Mehta Gambhir, a Mumbai-based mama of two, a former Lactation Counselor. Gambhir is not the only parent to have her children ‘addicted to screen’ in the time of this pandemic.

And hours of online school further added to the screen time tally. “Too much time and too little to do lead to more TV time. And since he’s been indoors he’s become more introvert-ish. He fears moving out and meeting people. In fact, he finds people a threat,” explains Gidwani, who worries about her son’s mental health.

Addiction to screens, moody behaviour, loss of appetite/eating disorders, fear of moving out and ‘acting out’ are the symptoms of a larger underlying cause – the pandemic-driven anxiety that has been suspended in the air much like the virus itself. “The lock-down took away our structures, our routines, which we find mundane… but these are the scaffoldings and rhythms of life, holding our children together, giving them a sense of security. This disruption of daily life has given a rise to anxiety among children,” says Child Psychiatrist and founder of Children First – Dr Amit Sen.

He tells The Health Collective that too much interpersonal contact within families led to the lack of personal space, institutional breakdown (for example schools being closed) led to a lack of purpose and identity, and the closure of spaces like parks and pausing of celebrations like birthdays that gave children a sense of joy and pleasure, left children with a lack of motivation and a sense of hopelessness. All these, in turn, have given rise to a sense of loss and grief. But how many parents are/were equipped to understand and address these new challenges faced by their children?

“The non-stop Zoom classes, the pressure to be seen to be learning and performing when all around them there is death, disease and stress has taken a toll on children and young adults in a way that we are refusing to acknowledge collectively,” says Natasha Badhwar, writer and author of ‘My Daughters’ Mum’. “The world as they understood it is broken and there seems little hope that we will be returning to pre-pandemic lives of safe holidays and boundaries between school, workplaces and homes. Their friendships are altered and there is an unending sense of isolation that is hard for parents and teachers to reassure them out of,” she tells The Health Collective.

Our world is broken today and we seem to have been forced to go against our natural instinct; something Aristotle spelt out centuries ago – ‘Man is by nature a social animal.’ And today this social animal and its pups are caged at home leading to mental health issues.

As per The Lancet study on Covid-19 and adolescent mental health in India, adolescents are experiencing acute and chronic stress because of parental anxiety, disruption of daily routines, increased family violence, and home confinement with little or no access to peers, teachers, or physical activity. Grief, fear, uncertainty, social isolation, increased screen time, and parental fatigue have negatively affected the mental health of children – UNICEF outlines the impact of Covid-19 on children’s mental health. According to another study (published by nature.com), conducted among teenagers in China (12 to 18 years old), there was a high prevalence of anxiety (43.7%) and depression (37.4%) during the COVID-19 outbreak, especially in females.

The pandemic has been cruel; to both parents and children – the immediate threat of the virus, the lockdown, the financial repercussions, the second wave, the lack of facilities, the lack of structure and life as we know it, and the many lives lost… Even as most tried to grapple with the immediate onslaught of Covid-19 and tried to make sense of the new lifestyle thrust upon them, not many have had the luxury to address their emotional and mental challenges. And the fact remains that there are vast socio-economic disparities within the country that impact parenting. Each strata faces its unique set of parenting challenges in addition to the common ones.

“With the first wave, some children saw close family members hospitalised or lost to Covid… That can be traumatic. The effects of trauma could set you into panic mode — completely freezing, panic attacks, complete breakdown emotionally… Following that, many chose ‘gaze aversion,’ that’s when you don’t look at the news and what’s happening around. But when you don’t process the information, it seeps in…” warns Dr Sen.

He adds that changes in their children’s behaviour (like mood swings, irritability and ‘acting out’), made parents wonder if their children were ‘going out of control,’ in turn, parents reacted by either using a firmer hand or looking away, thereby ‘making it worse.’

“I feel that adults need to acknowledge this loss and distress a lot more and not try to brush it off as a passing phase that children should be able to snap out of. Everyone needs support more than they need the pressure to perform and compete. We need to slow down, be gentle on ourselves, bring back laughter and light moments to our lives and not allow our devices to isolate us from each other, even as we are all stuck together physically till the threat of the pandemic lasts,” urges Badhwar.

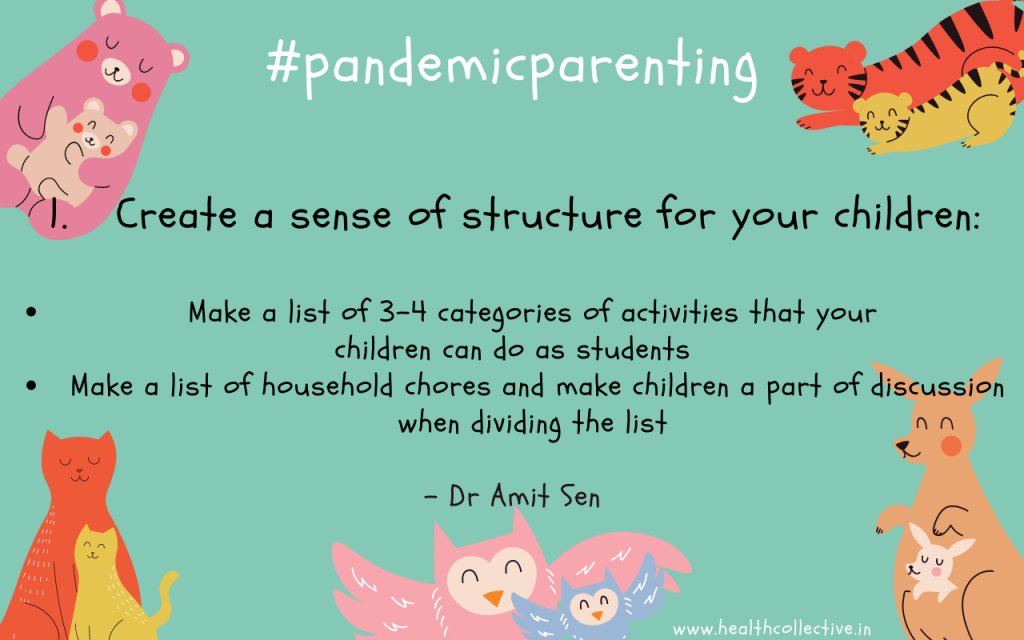

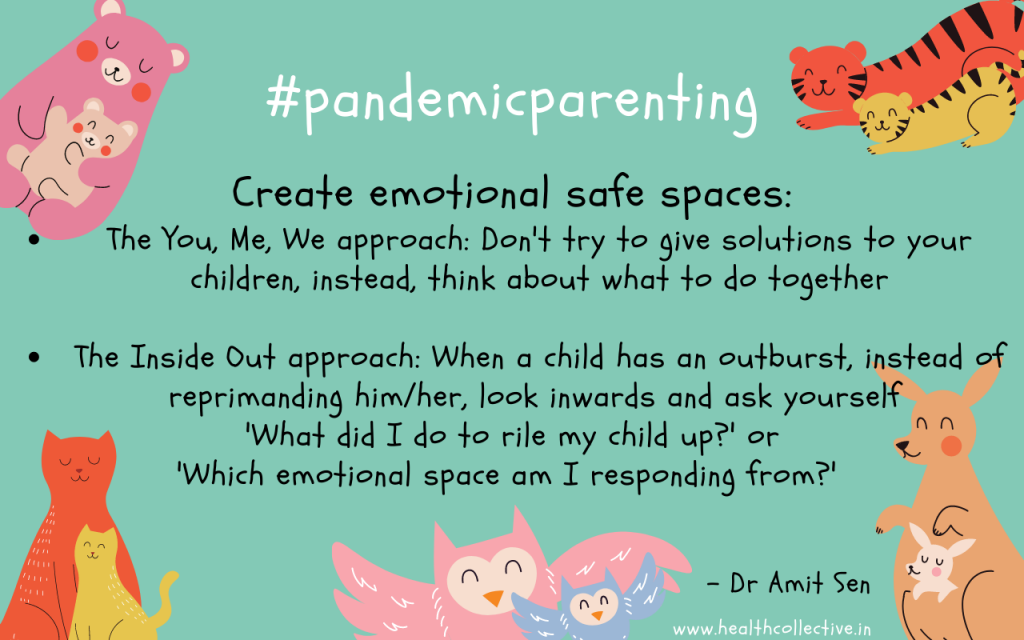

Tips and Recommendations by Dr Amit Sen (swipe for more)

Meanwhile, parents like Gidwani and Gambhir voice their concerns regarding the possibly long lasting repercussions of the pandemic on their children’s mental health, AND their social, physical and emotional health too. “I do think that a critical part of their childhood has been snatched away which will have repercussions on their mental health going forward. Just by keeping schools shut, and not taking into account the various other factors, the government is not being held accountable,” explains Gambhir who feels it’s essential to have children back in schools sooner than later. A thought backed by Dr Sen, “Around the world, experts have said that schools should be reopened. Remember, schools are not just about studying, they help children work on their motor skills, social skills and self-regulation… They learn about who they are… Can you imagine the disservice we have done to our children?”

Challenges of the pandemic not to be overlooked, Bhandari feels that the forced isolation came with its silver lining — “It taught them (children) how to be more independent, to help in household chores, keep their room/bathroom/study area clean, organise their time more efficiently, turn in their assignments, see closely how a house is run, become more sensitive to the plight of the immigrant workers, manage without outside help, manage without new art supplies, clothes, shoes, movies at the mall, meals out, and so on… They saw temporary shortfalls and yet we managed to ration our stocks and manage fine. I hope the experience makes them more independent, mindful of useless spending, compassionate, thoughtful, responsible, kind, law-abiding future citizens.”

When the lockdown forced families in, it also forced many parents to slow down and find that quality time to spend with their children. And while children saw their parents under the stress due to the pandemic, they also may have seen their parents rising to the demands of the situation and taking on new roles and responsibilities. “If they see how we handle a crisis like Covid, it becomes a roadmap for them to react in a similar situation, which could even be years later. Are we resilient, calm, positive, helpful, kind, resourceful in the face of a calamity or are we anxious, paranoid, in a panic and fearful? Children observe our reactions and internalise some of it and this in turn, shapes their behaviour,” says Bhandari, who feels parents set the tone for their children.

Our ability to accept and adapt defines our resilience. The theory of evolution is still in play; it is the case of survival of the fittest, not just physically but mentally too. And while children are often assumed to be resilient, the pandemic’s scars must not be ignored or glanced over. “The ability to adapt or learn happens when you are able to overcome the difficulty but if it continues… Children who have been through death, separation or abandonment and have felt a deep sense of helplessness, may carry emotional scars for life,” explains Dr Sen who confirms that he has witnessed an exponential rise in cases of depression, drug abuse and self harm among adolescents and young adults during the pandemic. He goes on to stress the need to create emotional safe spaces within families where children can freely share and be heard, “not lectured or given solutions. Parents need to listen to their children, not just with their ears but with their hearts and their whole being. And then, together think about what to do,” Dr Sen says, explaining what is termed as the ‘You, Me, We’ approach.

He also stresses upon the need to create a sense of structure in daily routines, to turn to good memories of the past when the future seems uncertain – to revisit old music, books, pictures, etc which give one joy AND most importantly, to live in ‘here and now’ by practising mindfulness.

Self care is the first step that the parents need to take before stepping up to meet their children’s needs. “Definitely prioritise your own well-being and be kind to yourself. Do not put pressure on yourself to constantly over-exert for your kids as unless you take care of yourself they also will not be happy,” says Gambhir. Echoing the sentiment, Dr Sen feels all parents must follow the emergency rule practised on flights – Wear your own oxygen mask before helping someone else.

Additional resources:

UNICEF’s toolkit for psychosocial support for children during COVID-19

About the Author: A journalist for well over a decade, Vanita Singh Fernandes is now a full-time mom and Strategy & Creative Partner at The Dallas Company.

ALSO SEE