The Mind-Body Connection: The Gut-Brain Axis and What it Means for You

Could the latest research on the gut-brain axis be just what the doctor ordered in enhancing our model of understanding and treating mental health disorders?

By Somi Das

This might sound familiar. On a bad day when nothing seems to be going right for us, we resort to eating our favourite ‘comfort food’ to restore a sense of mental well-being. Similarly, many people report an urge to excrete whenever they are under stress, or feeling anxious, or when they have to make a difficult decision.

There is actually robust science to explain these banal everyday events that somehow make a connection between gut states and brain states. In the last two decades, a number of studies have provided mounting evidence supporting a well-known folk psychology hypothesis – what happens in your gut affects your brain, your emotions and behaviour and vice versa. In the science literature this connection is known as the gut-brain axis.

Understanding this vital system equips us to look at mental health through a multi-dimensional prism and empowers experts to provide a holistic treatment plan for their patients. At the same time, popularising such findings can serve as physio-psychological education for people suffering from mental health disorders on the one hand, and on the other, help people with functional gut disorders – irritable bowel syndrome, dyspepsia, chronic constipation – potentially work out different modalities of treatment.on the other. It’s important to note that functional gut disorders are different from structural gut disorders in which the disease could be traced to organ malfunction or some other biological factor.

Editor’s Note: As always this information is meant to raise awareness, not to encourage self-diagnosis. Please reach out to trained medical professionals for your health concerns and needs.

Gut-Brain Axis and Mental Disorders

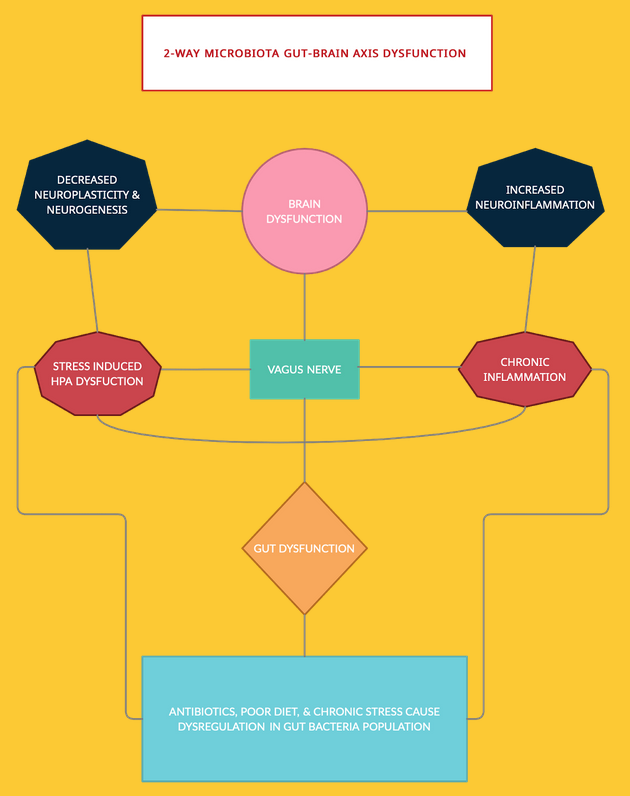

The Gut-Brain Axis (GBA) isn’t hinged on a single physical entity connecting the gut to the brain. A host of complex systems – neural, endocrinal and immune – come together to make this axis.

A set of cross-talking pathways connect the Enteric Nervous System that lines the walls of our digestive organs and the Central Nervous System, comprising the brain and the spinal cord. This makes communication possible between the cognition and emotional centres of the brain and gut activities, allowing the brain to influence gut activities and enabling the gut to affect mood, cognitive abilities and mental health.

The main nervous sensory connection from the gut to the brain is via the vagus nerve.

Explaining the important role this nerve plays in the functioning of the GBA, Professor at McMaster University and Director of Brain Body Institute, St Joseph’s Healthcare, John Bienenstock tells The Health Collective: “It is clear that the vagus nerve carries important information to various parts of the brain and influences cognition, memory and behavioural characteristics such as mood and anxiety. If the vagus nerve is cut below the diaphragm, specific influences of so-called beneficial bacteria (such as probiotics) on brain function and behaviour are prevented.”

The vagal activation theory has got researchers excited and led to the creation of a new field called ‘electroceutical’ manipulation to aid mental wellbeing. Explaining how these methods are being used in the US and Europe, Bienenstock says, “We are just beginning to accumulate evidence in this new field. Much attention has been focused on the possibility that stimulation of the vagus nerve might positively influence mood disorders such as anxiety and depression. The Federal Drug Administration in the USA and its equivalent in the European Union have licensed electrical vagal stimulation (which may require an implanted device) to treat depression. More recently, external non-implantable devices to stimulate the vagus in the head and neck have become available and claims are made that this may alleviate various forms of headache as well as possibly affect mood.”

HC EXPLAINER

- Your gut and brain are engaged in a two-way talk all the time.

- Dysfunction in neural, immune and hormonal pathways that connect these two vital organs are also correlates in mood disorders

- Patients of mood disorder being treated by psychiatrists and clinical psychologists complain of appetite disturbances, metabolic disturbances, and functional gastrointestinal disorders

- Similarly, patients of non-organic gut disorder who visit gastroenterologists exhibit heightened symptoms of anxiety and mood disorder

- Your gut is home to millions of bacteria. Some of them are friendly and others, disease-causing

- Dysregulation in the population of these “good bacteria” triggers immune and hormonal responses that affect your brain physiology, your mood and behaviour

- These disturbances can be traced back to gut microbiota abnormalities

- With these findings dietary changes, prebiotic and probiotic ingestion, exercise and relaxation activities, restoration of gut health, are being seen as complimentary treatment options for mental health disorders like Major Depressive disorder, eating disorders etc

Another major gastrointestinal component that holds power over the brain is the gut microbiome. The human gastrointestinal (GI) tract is home to a dynamic population of microorganisms, the gut microbiota. In fact, the role of the gut microbiota is so crucial that Dr Emeran Mayer, author of best-selling books like The Mind-Gut connection and the Gut-Immune Connection, renames the axis the “Brain Gut Microbiome (BGM) system.”

Gut bacteria that under normal circumstances performs the task of breaking down nutrients in the host body produces many neurochemicals. These neurochemicals and neuromodulators are used by the brain to regulate not only basic bodily functions but also mental processes like learning, memory and fluctuations in mood.

When it comes to our moods, many of us have heard of serotonin, a key hormone that stabilises our mood, feelings of well-being, and happiness. Well, 95 per cent of the body’s serotonin is manufactured by gut bacteria, according to experts, while only 5 per cent is produced in the brain. In the medical literature, serotonin is referred to both as a neurotransmitter and as a hormone that regulates activities like sleeping, eating, and digestion.

Serotonin deficiency is implicated as the chief neurobiological cause of psychological conditions, including eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, depression and other mood disorders. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors – a group of anti-depressant drugs – are the most commonly prescribed medicines to patients of mood disorders.

In addition to this, a rich (large in number) and diverse (greater number of species) gut flora is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the GI wall, which if breached, can trigger immune/inflammatory responses and adversely alter brain chemistry.

Explaining the dangers of dysregulation in gut population Emeran A. Mayer, MD and Distinguished Research Professor of Medicine G. Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress & Resilience told The Health Collective, “Dysregulations of the gut microbiome (“dysbiosis”) can lead to changes in this communication system resulting in structural and functional brain changes. Based on animal studies, and a growing number of human studies, there is a correlation between an altered gut microbiome and mood and behavior. One of the key mechanisms being explored is the “leaky gut”, in which gut microbes get access to the gut based immune system, leading to widespread immune activation in the body, including the brain. Diet, which is a major factor in influencing the gut microbial composition and function has been shown to improve outcomes in depression treatments.”

The role of pre-biotics in enhancing gut and mental health is being explored and findings have supported that these components have a positive effect on mood. Elaborating on this, Kolkata-based researcher at the ICMR-National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases Debmalya Mitra tells The Health Collective, “We talk about the benefits of ingesting probiotics. But what these friendly bacteria thrive on is prebiotics which are resistant starch. When the beneficial gut bacteria feed on prebiotics they release various psychoactive compounds like short chain fatty acid which have both mental and psychological benefits.”

The Psychosocial Roots of Functional Gut Disorders

The mutual tyrannical hold that the gut and the brain have over each other can also explain the high mental illness co-morbidity in patients suffering from inflammatory and functional bowel diseases.

In the absence of bio-markers, in the 1980s the Rome Foundation formed a panel of international GI experts to develop a standardised way to diagnose these diseases of the gut that had left most physicians scratching their heads. Rome criteria, first released in 1994 and revised multiple times since then, delineates a set of symptoms to diagnose a cluster of gut diseases now known as Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDs).

The pathways underlying the symptoms are very similar to the ones implicated in mental health disorders like motility disturbance (diarrhea and constipation), visceral hypersensitivity (neural pain), altered mucosal and immune function (inflammation), and most importantly gut-brain dysfunction triggered by disturbance in gut flora population.

All these symptoms can be aggravated or perpetuated by psychosocial factors like alexithymia (inability to describe what one is feeling), catastrophization (imagining the worst possible outcome to an event), ongoing work or any other life stress.

Explaining the underlying psychosocial causes of FGIDs Delhi-based senior gastroenterologist Dr Aneesh Gulati tells The Health Collective, “A majority of the patients I see at the OPD present with symptoms of functional Gut Disorders. FGIDs can be diagnosed only after having ruled out organic etiology through tests. Patients of Irritable Bowel syndrome and other functional gut disorders also present with anxiety, depression, phobias, and somatization. Many patients have had a history of child abuse. Another underlying cause of FGID are issues related to sex. Often people diagnosed with FGIDs have lower sex drive.”

Even though FGIDs are not strictly categorised as psycho-somatic disorders (diseases of the body with psychological roots), there is consensus on the fact that stress response of the body plays a key role in worsening these conditions.

“These patients are either going through a major stressful situation in their life or have experienced greater lifetime stress compared to (the) ‘normal’ population. One scientific evidence for this is the fact that their gut is more sensitive to Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), a peptide released in the brain as part of body’s stress response. When you administer CRF on normal population it doesn’t affect them. However, when the same is administered on patients with FGIDs they experience abdomen pain and higher motility,” he says.

Following these findings, in addition to dietary intervention, gastroenterologists, who have now earned the sobriquet of “counsellors of the gut” prescribe breathing techniques like Pranayama, relaxation techniques like Yoga Nidra, biofeedback (using devices to increase awareness of tension in body), and psychotherapy. Ayurvedic interventions are also known to be effective in cleansing the gut and helping stabilize emotional states associated with inflammatory conditions.

Need For More Research

On the other end of the spectrum, it looks like mental health practitioners are yet to integrate the findings of these studies in their action plans. There are plenty of reasons for that – including perhaps the need for more research. For instance, the research literature throws encouraging results on the efficacy of prebiotics and probiotics and fecal transplant in treating mood disorders. However, despite rich anecdotal evidence available in the research literature, these studies are at a nascent stage and most of them are done on animals.

Highlighting the factors holding back clinicians from applying these findings in their practice Bienenstock says, “Various beneficial bacteria and combinations thereof have been claimed to have positive effects in clinical disorders or to maintain mental well-being. While some of the animal experiments do strikingly show this type of effect, the information from clinical work is less convincing so far. There is considerable effort being made to try and narrow the gap between experimental evidence and clinical work but this has not yet reached the situation where unequivocal conclusions can be drawn.”

Further, gut flora is community- and culture-specific. The results from the studies have to be replicated at a large scale across a diverse population accounting for geographical differences, and including all ethnicities and cultures to have any substantial health benefit as an alternative treatment modality.

In India, there are very few studies on indigenous microbiota. The first comprehensive report on this subject was only published in March 2019 issue of GigaScience. “The current studies show that Indian gut microbiome is very different from the gut profiled in Western studies. The diversity comes from our plant-heavy platter. The implications of such a finding are still not properly understood. The fact that the Indian population is experiencing an alarming increase in cases of mental disorders and digestive disorders should drive more research in this direction,” Mitra tells The Health Collective.

Even with these limitations, the findings are robust enough for mental health professionals to take notice.

While in the West, mind-body based therapies, nutritional psychiatry, integrative psychiatry and other forms of holistic and multidisciplinary treatments are becoming commonplace, India is yet to catch up on this trend.

Elaborating on the lack of integrative and holistic avenues for healing for patients in India, Dr Aneesh Baweja, MD – Psychiatry, says, “It is not unusual for patients at my clinic to present with gut symptoms only. They come through referrals from gastroenterologists who have not been able to make any progress with their gut problems. We take the usual route of prescribing antidepressants and anxiolytics to patients, with additional psychotherapy. Even though bi-directional communication between the gut and the brain is a well-established fact in the research literature, patients only have two channels — either show up at the psychiatrist’s clinic or go to a gastroenterologist. They are continually being referred back and forth, but the instances of GI specialists referring to psychiatrists are higher. The irony is that traditional Indian medicinal systems like Ayurveda have always known the gut to be the source of all disorders, including mental disorders.”

This is not to suggest that all mental illnesses can be located in the GBA. That would be an over-simplistic approach to treating something as complex as mental illnesses as confounding socio-cultural factors play a huge part in their manifestation. However, what is also true is that the GBA research findings are in sync with the axiomatic assumptions of the medical or biological model of explaining mental illness – that diseases of the mind are in fact, diseases of physiological or chemical disturbances in the brain. Then it is only logical to probe Gut, nicknamed as the second brain, as a possible site of psychopathology.

About the Author: Somi Das writes on mental health, behavioural sciences, and art & culture. She did her internship for her Master’s Program in Clinical Psychology from West Delhi Psychiatry Centre closely observing in-patients of schizophrenia, drug addiction and mood disorders.

Twitter: @Somi_Das | Insta: @the_millennial_pilgrim

BY THE SAME AUTHOR: