Your Stories: How to Travel Light

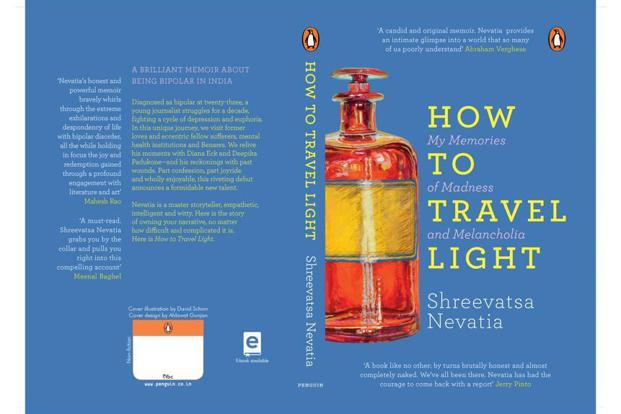

The Health Collective is delighted to feature an interview with Shreevatsa Nevatia, author of How To Travel Light: My Memories of Madness and Melancholia (Penguin RandomHouse India, 2017). We highly recommend the book, which releases October 25, 2017 in India.

Nevatia speaks to Amrita Tripathi about his book, his journey, and some of the very personal and difficult moments along the way… as well as the solid backing and support he has had from loved ones.

- What are some of the thoughts going through your head now that the book is out for everyone to read? Relief? Worry about being judged? Anything you can share …

Working as a journalist, I had always been conscious of my audience. Writing a memoir, I realised very quickly, required a very different approach. Authors invariably sound disingenuous when they say they have written a book for themselves, but I can say this—I wouldn’t have been able to write How to Travel Light if I had periodically stopped to ask, “What would she or he think?”

This is the story of my life as I remember it. I have judiciously considered each of my memories, and for what it’s worth, I can now say, “I know this much to be true.” There is some relief in having said it all. The experience has been undoubtedly cathartic, and it is perhaps because the book inadvertently did me so much good that I don’t find myself very worried about people’s judgements

Besides, I believe that those who judge someone by their past do so in shorthand. I recognise the Shreevatsa I write about, but today, I am someone else. I hope readers of the book factor that in. There is, though, a kind of judgment that makes me anxious. I want people to think the book is well written, that it has literary value. I confess to vanity.

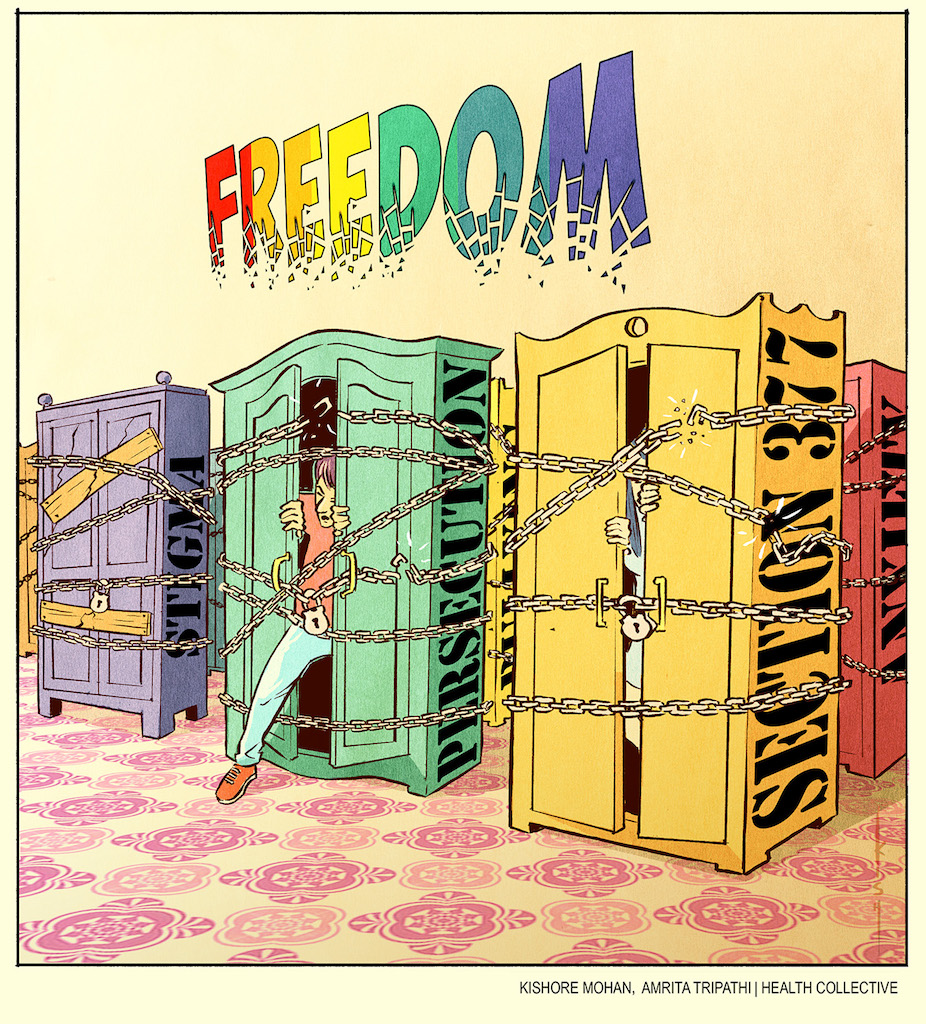

- Contributors on our site The Health Collective share stories about living with BPD, or schizophrenia, coping with depression and more… What would you like to tell them? What to your mind is the value of sharing our stories and normalising the conversation around mental health, especially in India given the stigma we still see?

Ten-and-a-half years after being diagnosed bipolar, I have found that nothing defeats stigma better than the act of speaking.

I have to compliment you and The Health Collective for providing such an enabling platform to those who are struggling with mental health afflictions. To clear doubt and misconception, you need confession and conversation. Though unique, there is great comfort in knowing that your condition and subjectivity isn’t without precedent. If one can only come to know oneself in relation to others, we need to first ensure that a wide cross-section of voices gets heard.

I have often used stories to map the tumult of my own mind, and I do think we need to invent a world where narratives of those living with mental health conditions are part of a more common discourse. Nothing would alleviate pain more.

To the contributors on your site, I could only say, “Please keep writing,” but for your readers, people who aren’t necessarily afflicted, I’d really like to add something very small—“Please, let’s talk.”

(The Health Collective)

- How do you describe your phases of mania, for those who haven’t yet read your book? How did it manifest (and sometimes let your friends know that you needed help)?

Mania is seductive. There are some tell-tale signs. It all starts with losing sleep. Feeling a boundless energy, I’d start to join dots that don’t necessarily belong on the same page. Freud, Kafka and Krishna, I would argue, have all said the same things and arrived at the same conclusions. I have felt Julie Andrew’s Maria in The Sound of Music is my perfect parallel. When manic, my appetite for all things amplify — books, films, music, life, love. This expansiveness is, however, short-lived. Very soon the world isn’t impressed by your plans. It is instead confounded.

Once I’d meet those familiar roadblocks of misunderstanding, I’d turn megalomaniacal. From being nimble and playful, my language would turn didactic. Pleasure and levity would become my entitlements. My demands would be extravagant, and I would feel no remorse when berating family and friends for what I thought was their limited supply. I would alienate my support system. I would never seek help. Thankfully, they never once gave up on me.

Also Read: Your Stories on The Health Collective

- You did experiment with tapering off from your medication, given the side-effects… Any advice on what’s helped you in the long run, come to terms with your condition?

The side-effects of drugs like Lithium and Depakote can be very debilitating. Your hands tremble uncontrollably, and it becomes impossible to hold a plate or a cup of tea. You start gaining weight, you feel sluggish, and both your mind and body feel oppressively heavy. Nostalgia is always dangerous, and in my case, it was doubly so. It made me either taper my medication, and sometimes, it made me stop taking my pills altogether.

I would yearn for a former self that I felt looked and thought better. I realise I was chasing something and someone altogether impossible. I was only able to escape this cycle when I began describing the extent of the side-effects to my psychiatrist.

He would hear me out and tailor my prescription accordingly. It takes a lot of trial-and-error to find the right balance of drugs. I’m more functional today because I swallow my Lithium, and also because I was forced to rediscover patience.

Also Read: Severe Side-Effects, One Woman’s Journey Through Depression

- You write very movingly also about the feelings that are evoked, when you talk about your family visiting you, say, or your ex-girlfriends… What are some of their thoughts on this book and your journey?

An anecdote will perhaps answer this question better. Having finished writing the book, suddenly aware that I had said all I could, I asked my mother to read my work. I didn’t want her to be blindsided by the memoir’s content or by the feedback it might receive.

I remember saying, “Ma, I worry that someone is going to ask you why I wrote all this.”

Her response was even. “I’ll say that you wrote it to become better.”

I pressed on. “But I didn’t have to publish it, did I?”

She replied, “You are publishing it so that other people can read it and feel better.”

My parents, doctors, friends, even my ex-girlfriends, have been nothing but encouraging. They have all seen me at my worst, and I think most of them were just relieved when they saw me do something I’ve always relished doing. They were all glad to see me write.

- What was the hardest part for you? (You write about guilt and shame… can you expand on these feelings and doing away with the negative feelings) And the hardest part of your journey for your parents?

Waking up in hospitals and mental health institutions has undoubtedly been the hardest part of this journey. When your mind begins to condone excess, exhausting itself in the process, a break from society is beneficial. But internment does invariably begin to feel like punishment, and I think it is that decision to put their son away which has been the most difficult for my parents. Each time I have found myself confined, I have regretted my manic aggression and irresponsibility.

It isn’t always enough to say, “That was not me, that wasn’t me at all.” My delusions have always found an audience. My loved ones have witnessed my debilitation, so there are still times when I wish I could expunge all those memories.

ALSO READ: D is for Depression: The Shubhrata Prakash Interview (Hindi)

- If there were three or four things you would share with families or loved ones of those suffering from bipolar disorder, what would those be?

- Bipolarity doesn’t have a cure, but thankfully there is enough medication that helps manage the disorder. It seems too much of a stricture at first, but if one does persist with one’s pills, gets at least seven hours of sleep, and stays away from drugs, lucidity does finally become possible.

- Therapy might not yield instant results, but it does slowly give you the ability to look at yourself from both, the inside and outside. There is much relief that such consideration can bring.

- We bipolar patients demand a lot from our families and friends. Our loved ones often need a reservoir of love and patience in order to cope with our turbulence. The only thing that I can ask of them is probably this – please do not let that reservoir dry up, and sometimes, do play along.

- How does one even begin to come to terms with the child sexual abuse you went through?

The trouble with child sexual abuse is that it seems too dastardly an act to be true. Growing up, I asked two questions – “Why me?” and “How could this have happened to me?” I only started coping when I changed my line of questioning, when I stopped looking at myself as a victim, and when I started looking at my own hardship as common.

The #MeToo Campaign, for instance, only proves that sexual assault is all too widespread, but like a friend pointed out, it again puts the onus of confession back on someone who might not want to make public her trauma. Writing about my abuse certainly helped me draw a line of sorts, but what helped me more was psychoanalysis. I found in Freud and my psychoanalyst an understanding not just of my victimhood, but also of acts we often think are too depraved to theorise.

Also Find: Child Sexual Abuse Helplines and Other Resources

Note: Views expressed are personal. Material on The Health Collective cannot substitute for expert advice from a trained professional.

How To Travel Light will be available for sale from October 25, 2017; You will be able to read an excerpt right here on The Health Collective