A Toast to the Ones We Lost on the Way

By Chintan Girish Modi

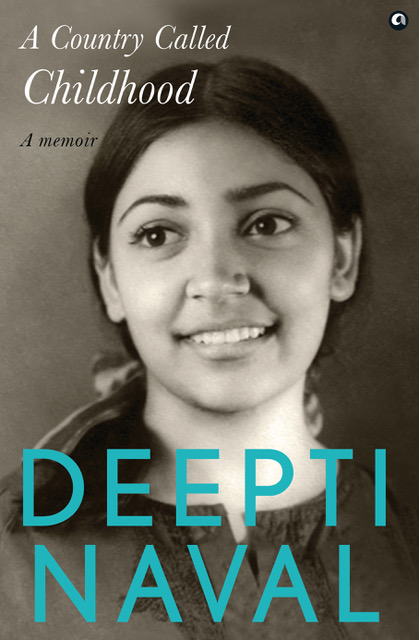

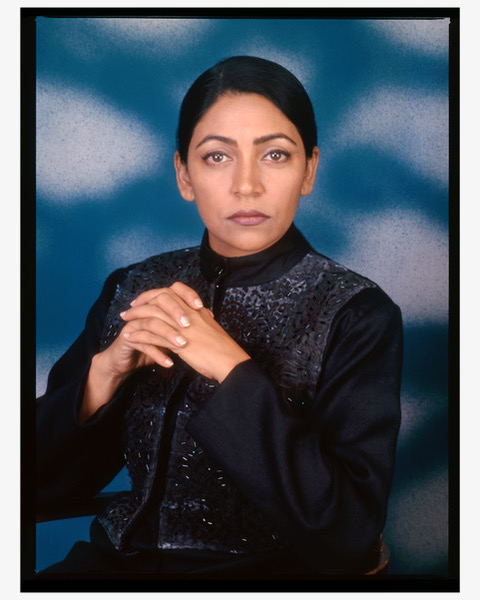

Actor-painter-filmmaker Deepti Naval talks to The Health Collective about the part of her memoir A Country Called Childhood that deals with childhood trauma.

What must it feel like to have a close friend sent to a psychiatric ward? Actor-painter-filmmaker Deepti Naval had this experience when she was a high school student. She writes about it in her memoir A Country Called Childhood, published this year by Aleph Book Company. In this interview, she revisits her childhood and adolescent years in Amritsar in the late 1960s, her decision to study psychology as an undergraduate in the US, her sensitisation to the experiences of gay men and lesbian women in the US, her inner life as an actor, her journey with depression, and the intersection between her artistic explorations and her mental health.

In A Country Called Childhood, you write about your friend Neeta who was sent to a psychiatric ward in a hospital. It must have been hard to revisit those memories…

Yes, it was but one has to work through things that seem hard and challenging. Neeta was an important part of my life in school; she was full of joy and affection. I was concerned about her but I did not understand her mental condition. She had a split personality, and her lesbian orientation made things even more complicated for her. Our society failed her because it was not evolved enough to support people with different sexual preferences. I am glad that things are changing now. It’s high time! Had she been in a different environment, she would have blossomed. We wouldn’t have lost her so early.

Did your decision to study psychology at Hunter College in New York come from a desire to understand what Neeta was going through?

I don’t think that there was a direct link between the grief I felt about Neeta, and my decision to study psychology, but it must have certainly been a factor shaping my thinking. My friends and I were distraught when the nuns running our school sent Neeta away to the hospital. We felt let down, and did not know how to handle it. Neeta was different but she was one of us. We were hugely protective and we were worried when she tried to harm herself. I did want to understand what she must have gone through. Mental health is so poorly understood. The human mind is a wondrous thing but it is also such a mystery despite all our scientific progress. I continue to be interested, and keep learning.

What did your college experience teach you about the lives of lesbian women?

My close friend Neeta happened to be a lesbian, but that concept was completely alien to me in those days. That changed only after I went to New York. This might sound outlandish today because there is so much visibility and awareness but it was uncommon during my childhood and adolescence for someone living in Amritsar to know girls or women who identified themselves as lesbian. I met gay men and lesbian women at college, and most people found it quite easy to accept them. Apart from psychology, I was also studying painting, astronomy, American theatre, and poetry. I encountered the sensuous love poetry of Sappho in my poetry class, (who came from Lesbos and that’s where the word ‘lesbian’ comes from) and I thought of how affirming it would have been for Neeta.

You have explored the stigma around homosexuality in your work as a filmmaker…

Yes, the premise of Do Paise Ki Dhoop Chaar Aane Ki Baarish (2009), was about how a sex worker, a gay man, and a disabled child come together and how a bond gets solidified between people who are cast away by society. I directed the film and interpreted it my way but the basic story came from writer Dharamveer Ram. My mind is that of an explorer. I have a great curiosity and empathy when it comes to people who do not ‘fall in line’. I can relate to it at some level because I was never someone who was looking for a normative life built around the idea that shaadi ho gayi toh zindagi guzar jaayegi (one will sail through life since one has the security of marriage to latch onto).

How do you take care of your mental health?

I have gone through major bouts of depression, ups and downs in my personal and professional life. As a student of psychology, I had a language and context to make sense of these experiences. I also knew that I would have to rise up on my own after hitting rock bottom. Painting and poetry have saved me. If I was just an actor, I would have cracked up by now. Actors go through emotional turbulence all the time because they draw from deep within themselves. When they tap into personal experience, they have to be alert about where the material is coming from. Sometimes, the memories are lying buried; when they come to the surface, they can bring up a lot of emotions.

Can you recall any character that was particularly tough to disassociate from after you had done all the work of understanding it, preparing for it, and eventually playing it?

My role as Beena in the film Main Zinda Hoon (1988), directed by Sudhir Mishra. This person lands up in a mental institution. Her dead father shows up to pull her out, or so she imagines. Instead of looking at the individual as flawed or deficient, there was an attempt to show that circumstances can drive you to a point where you lose a grip on yourself and the world around you. While preparing for an earlier film called Ankahee (1985), which was directed by Amol Palekar, I visited a lot of hospitals and saw much suffering. I have spoken about this experience in my INKtalk — someday, I will write about my observations at one of these institutions.